For many people, the destruction of wildlife goes on deep in the background of our lives. Wild animal populations have dropped more than 60 per cent since 1970 and for the most part, humans haven’t noticed. But every now and then, we are forced to look. As 2020 began we were scrolling through pictures of koalas, scorched and bloated by bushfires. We are still reading about the last Kangaroo Island dunnarts and regent honeyeaters, cornered as their tiny remaining habitat burned, and the 111 other species the Australian government tells us have been pushed to the brink by a disastrous summer.

All of these deaths are entangled with – caused by – almost everything we do: growing food, making clothing, building houses, travelling from place to place. They are enmeshed in the culture we make. Every human enterprise, profound or grotesque, is compromised.

What does it mean to watch as human society slowly devastates wildlife populations around the world, to watch as climate change–fuelled bushfires, habitat destruction and hunting push them into extinction? What kind of art can make up for what we’ve done? Can any kind of art make it stop?

For artist Lucienne Rickard, crisis hit in 2019. In March, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Her work is fine, detailed drawing on a large scale: the thought of losing her motor skills was terrifying. Rickard didn’t know how long she would be able to keep making art, and she wanted to do something important with the time she had left. In June, she saw the ABC Four Corners program Extinction Nation, and was enraged by the Australian government’s complicity in the destruction of so much native wildlife. She had found her subject.

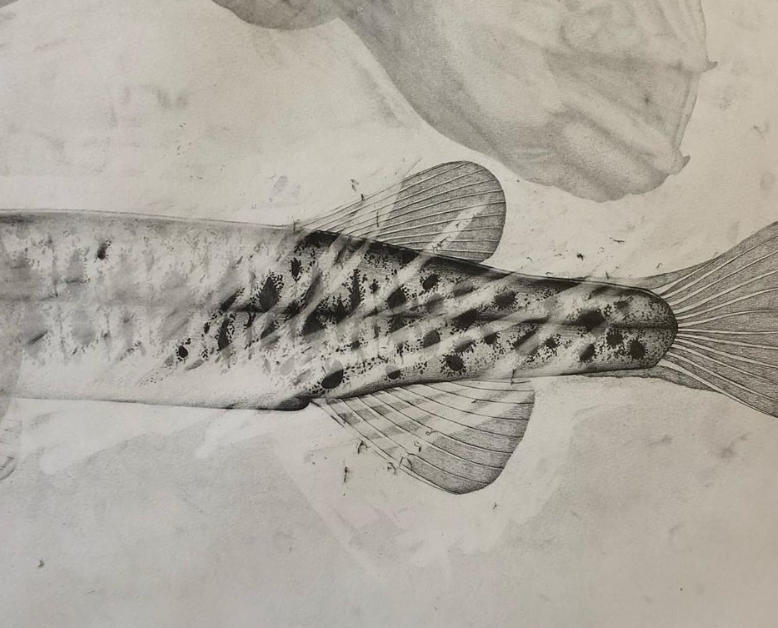

Extinction Studies began in September 2019 and will run until September 2020. For the duration of the project, Rickard stands in the foyer of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) in Hobart, drawing an extinct animal or plant, often at many times life-size. She is there at least five days a week, drawing with a 9B pencil for six hours a day. When each drawing is done, which usually takes days, she erases it and begins another on the same piece of paper, building up a palimpsest of almost invisible creatures.

The project is commissioned by Detached Cultural Organisation, also based in Hobart. Detached’s founder, Penny Clive, has a reputation for caring intensely about environmental issues, and Rickard has produced work for her previously about Lord Howe Island shearwaters killed by plastic pollution.

Rickard began Extinction Studies hoping she could make a difference: that she could make people realise the scale and horror of extinction, and that they would be moved to take their own action. She wanted to reach people beyond those who visit the small commercial galleries where she usually exhibits.

“I should really be drawing in a shopping centre to reach the people I most want to reach,” she says. “People who come to museums are obviously already interested and open-minded. But at TMAG I do get lots of people from cruise ships coming in, who often haven’t really thought about these things before.”

As the project has progressed, though, her thoughts about its purpose have changed.

“More and more I feel like it’s about just acknowledging the individual species existed. Throughout my career, I always felt that I owed my subject matter for being able to draw them. This is heightened with Extinction Studies. There’s guilt mixed in there too. I have to draw them in as much detail as I can because they deserve that; because it’s the right thing to do. The erasing is almost like a funeral. I know that sounds really over the top, but that’s what it feels like to me.”

When I spent the day with Rickard at TMAG, she was drawing the St Helena giant earwig (Labidura herculeana), once endemic to the small, remote island of St Helena off the coast of Africa but driven to extinction by introduced mammals and the removal of its habitat – rocks – by the construction industry. The earwig was the world’s largest, growing up to 8 centimetres long. Rickard has written about it on her Instagram. “Unlike most non-social insects, earwigs are doting mothers. They ritually clean their eggs and help their offspring hatch. Once out, the mother feeds her young regurgitated food and allows them to sleep underneath her … In the midst of the Australian bushfire crisis the media has focused on the toll to humans and iconic species like koalas. Insects such as earwigs play a vital role in ecosystems. We are yet to count that cost.”

The paper sheet is dense with the whispered remnants of the species Rickard has drawn since September, and scaled with texture where her eraser has rubbed away the surface. She’s been pleased, she says, with the unexpected ways the texture has worked with her pencil. While she had initially planned to keep using the same sheet of paper throughout the year-long project, she has now begun drawing on a second sheet, which she will take with her to the Sydney Biennale in March. The first is hanging at Detached, in The Old Mercury Building in Hobart.

“When we moved it to Detached … I definitely thought I would use the first one again,” she says. “But now drawing on it again seems wrong somehow. I wish I could say why.”

She’ll continue with the new sheet for as long as possible. “I’ll just see how long I can keep working on it – I would like it to wear even more than the last.”

The species take hours or days to draw, and mere minutes to erase. The golden toad (Incillius periglenes), once native to Costa Rica and declared extinct in 2009, took 60 hours to draw and six minutes to erase. “You can swipe at the drawing in big aggressive gestures and leave white tracks right through heavily rendered areas almost effortlessly,” Rickard says. And this erasing – in many ways the entire point of the project – has proven very controversial.

“On the whole, people are far more horrified that I’m erasing the drawings than they are that the species I’m drawing have gone extinct. One man got angry enough to tell me I was committing sacrilege by erasing art, even though I’d created it in the first place. We’re more sentimental about the things that humans create, about human endeavour, than we are about whole other species.”

Our adulation of human culture seems to blind us to the many, many cultures we are ourselves erasing. When Rickard was drawing the Least Vermilion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalis dubius), which once lived on the island of San Cristóbal in the Galápagos Islands, she wrote about it: “Flycatchers are not capable of mastering new songs, they are born with a preset melody – a quirk of evolution like pearls made from grit. The Least Vermilion Flycatcher sung its own song, different from all the rest.”

“When we’re thinking about extinction, often we talk about the role species play in ecosystems. They all do a job, they’re all necessary. But what about the pearls, the strange moments of beauty that have their own innate value? We’ll never hear this Flycatcher’s song again. That song is a loss. It’s just one little stitch that’s been dropped from the richness of existence.”