At first it was catching COVID that scared me. But now, it’s how quickly everything has collapsed.

Apparently, some part of me still believed that here in Australia, when it came down to it, governments would step in and protect us. All the evidence is against this belief, of course, but sometimes we hang on to irrational ideas just so we can get on with our day.

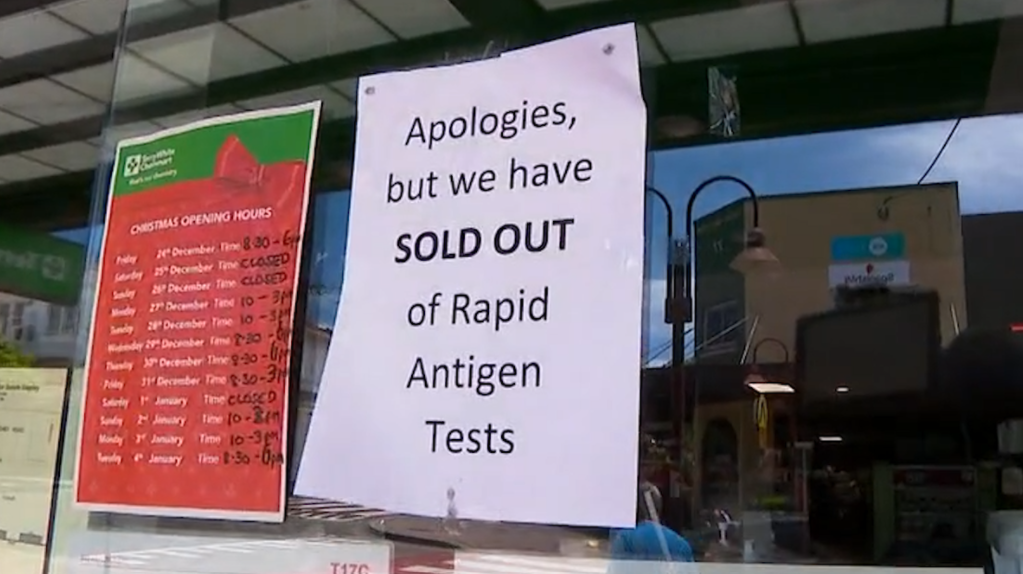

Right now, I’m letting go of that belief. Because today we’re faced with a situation where an already existing, cheap-to-produce, simple-to-distribute technology that we need to keep us safe and which it was easy to predict we’d need, just isn’t available. Those without money can’t get it at all. Even those with money are spending half their lives checking websites, going door-to-door, hoping to get their hands on one that they know will be hideously marked up, because the market charges what the market will bear.

RAT tests exist. The government knew we would need them and keeps telling us we have to have them. They don’t care that we can’t get them, and they certainly don’t care that people in remote rural locations or people without money or people who can’t travel might never be able to get them.

There are ways around the problem. You assume you have Covid already, you stay in your house (if you have one), you take leave from your job or work from home (if you have that kind of job, which you probably don’t), you wait it out (if you or your kids aren’t already racked with symptoms and desperate to know if you can please be seen by someone who might help). All this will pass.

Until next year when it’s bushfire season and everywhere is swathed in smoke again. Remember when you couldn’t get a P2 mask anywhere for any money in the summer of 2019-20? Do you think it will be different next time? We know there will be bad bushfires again, and soon. We know there will be smoke. We know smoke kills people, both in the short-term and the long. We know masks are a cheap, simple, available technology that can help keep us alive. We can predict we’ll need them, which is fine if you’ve got enough money handy to stockpile some now against that eventual future. But what if you’re a musician and all your gigs are getting cancelled and the last thing you want to do right now is buy something you might need in 2023? What if you’re a single mum living in your car with your kids—where are you even going to store your mask stockpile, just say you could afford it? What if you live in Smithton, north-west Tasmania, and you don’t have a car and you can’t get to a Bunnings and you can’t afford the internet to buy a mask online?

And what about a few more years from now when we’re in our next big drought, even worse than all the previous droughts, and our cities start running out of water. And then they do run out of water. And even though, like a RAT—even more than a RAT—water is something we quite clearly need, you’re trudging the streets trying to find someone who’ll sell you a few litres of water at a price you can afford to pay.

In 2014 I wrote a book about climate change, designed to help you prepare yourself for heatwaves, droughts, floods, fire, supply-chain breakdowns, panic, grief, despair. My co-author, James Whitmore, and I pointed out that it would be a lot—a LOT—better if governments would step in and do some of the work of adapting our society to better cope with climate change, but that it wasn’t looking likely they would. Still, I hoped. After the fires in 2019-20, I hoped a little bit more. Surely such a massive disaster with such a clear signal of climate change would get things moving. Surely serious thought and funding would be dedicated to scenario planning, to shoring up supply chains, to ensuring those most in danger were prioritised for protection. The government did set up a $50m fund to mitigate future disasters, but by the end of the 19-20 financial year, none of the funds had been distributed. This came on top of their de-funding of Australia’s National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility in 2017.

In January 2020, the Prime Minister said of climate change, ‘We must build our resilience for the future and that must be done on the science and the practical realities of the things we can do right here to make a difference,’ which was good news considering that a couple of years previous we’d been ranked 54th in the world for our climate change preparedness and unlike 71% of OECD countries, we had no national climate change adaptation plan.

Perhaps the plan released late last year will set us on the right path. But a plan is one thing, and the evidence of how our governments prepare for and execute a response to a foreseeable emergency is another. That evidence is all around us right now, and it’s not promising.

I would like to live in a country where the government has the interests of its people at heart. I would like to live in a country where people with more money (I include myself) are taxed more, and that money goes to fund a well-resourced public service, disaster recovery agencies, health-care services, public transport and a welfare system that whole-heartedly supports those who need it. I would like a government that, rather than caring about lining its own pockets and the pockets of its mates, has an ethic of care for the people whose lives it holds in its hands.