I love apocalypses. In the ’80s I spent sleepless night after sleepless night worrying about whether the submarine information relay tower near my house would be a Russian nuclear target. I ruined a family holiday to New Zealand with my relentless insistence Mount Tongariro would erupt from dormancy (I was right, but 32 years ahead of my time). I dreaded Christmas visits to my Adelaide grandparents (from safely landlocked Canberra) because of the increased risk of tsunamis. So it’s no wonder I was gripped by Annabel Smith’s post-peak-oil dystopia, The Ark.

The Ark takes place in a seed bank bunker in the Australian Alps, where a few survivors have taken refuge from ‘the Chaos’ tearing apart the world outside. But power struggles and intrigues mean life inside is almost as treacherous as it is outside.

The Ark takes place in a seed bank bunker in the Australian Alps, where a few survivors have taken refuge from ‘the Chaos’ tearing apart the world outside. But power struggles and intrigues mean life inside is almost as treacherous as it is outside.

I spoke to Annabel about what inspired her to write this particular apocalypse.

We’ve both written books about an apocalypse in Australia, and I’m currently writing a non-fiction book about the same thing. Because the book I’m writing now is non-fiction, I have to do research and try to extrapolate to a believable future Australia. But how did you decide on the version of apocalypse – one that happens in the 2040s, and has a lot to do with peak oil and with the collapse of forest systems and crops – that you went with in The Ark?

The Ark was inspired by Adrian Atkinson’s essay ‘Cities After Oil’. Atkinson goes into great detail about the possible outcomes of our unpreparedness for post-peak oil, and proposes some timeframes which seemed more than plausible, so I based my apocalypse and its setting on his predictions.

During your writing did you think about what you’d do in an apocalypse? Would you rather be in a bunker with your workmates and immediate family, cut off from everyone else, or out in the world?

Both scenarios are horrible in their own ways. Given some of the places I’ve worked, the idea of being locked in a bunker with colleagues could be a fate worse than death! But of course, not really. Even the most idiotic and annoying people in the world couldn’t be worse than what would happen outside. When I think about trying to survive in a lawless world, I think of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and I think of the child in that novel as my own son and I can’t imagine anything worse than the horror and anxiety of trying to protect him, both psychologically and physically, from the terrible things he’d be exposed to. So, the bunker wins.

I love that The Ark is set in a workplace – given most of us spend most of our lives in offices, it’s amazing how little fiction happens there. And one of the things I loved most was the level of detail you reached in creating the electronic communications used by Ark employees. How did you come up with these?

Creating the electronic communiques was one of the most enjoyable parts of writing The Ark. The kinds of communiques I created was driven by what I needed to say. Some version of emails and text messages was an obvious choice, because they are the ‘bread-and-butter’ of our communication. The comments thread of blog posts enabled me to give readers a view of the outside world. The difficulty of an epistolary form is that the narrative cannot tell you what people are doing. Certain scenes were impossible to convey through the other written forms I had developed, which is why I decided to include the conversation transcripts. They permitted both action and tone.

Other than On the Beach, very few big-name dystopian novels are set in Australia. Did you have any second thoughts about situating your seed-bank bunker in the Snowy Mountains?

None at all. When you are walking a well-trodden path like post-apocalypse/dystopia, anything that brings new life to the genre is a positive, as I see it, so a fresh setting seemed like a plus to me.

I’m guessing you’d describe yourself as politically progressive. Do you have any hope that The Ark might shift political views at all, might make people more concerned about what we’re doing to the environment and more likely to, say, vote differently next time around? Or is it just fiction for the story’s sake?

I regret to say that I don’t believe fiction will change people’s behaviour, not because it’s not powerful, but because I believe the human race has its head so firmly buried in the sand about this issue that nothing at all will change people’s behaviour. I don’t think people are going to change until they start to be directly impacted by climate change, i.e. continual power outages, water not coming out of their tap etc

And finally, which apocalypse do you spend most of your time worrying about: climate change, nuclear war, peak oil or a deadly pandemic? I’ve provided a chart of my lifelong worries below, for perspective.

Nuclear war doesn’t really feature in my list of anxieties, though I remember worrying about it as a child. With both post-peak oil, and climate change, the gradual nature of the potential impact means it is more likely to affect my son’s generation and I worry about that. Should I be teaching him to hunt and shoot and build a shelter out of twigs and leaves? However, the apocalypse I fear most is a pandemic, partly because I just finished reading Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven, which explores that very topic, and also because. according to historical precedents, we’re overdue for a pandemic.

Annabel Smith is the author of Whisky Charlie Foxtrot, and A New Map of the Universe, which was shortlisted for the WA Premier’s Book Awards. Her short fiction and non-fiction has been published in Southerly, Westerly, Kill Your Darlings, and the Wheeler Centre blog. She holds a PhD in Writing, is an Australia Council Creative Australia Fellow, and is a member of the editorial board of Margaret River Press. Her digital interactive novel/app The Ark has just been released. Connect with her on Facebook and Twitter.

nike sulway

November 24, 2014 at 5:47 pmGreat interview. *The Ark* sounds really intriguing. I hope it attracts a wide and enthusiastic readership.

Jane Bryony Rawson

November 25, 2014 at 10:49 amMe too!

knrwrites

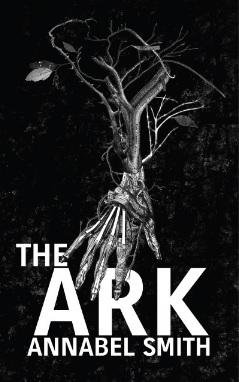

December 12, 2014 at 11:44 amThat cover is simply Gorgeous!

Also, glad to know I’m not the only one with an imagination skewwed toward the apocalyptic.

Jane Bryony Rawson

December 12, 2014 at 11:47 amIsn’t it amazing? The book lives up to the cover too.